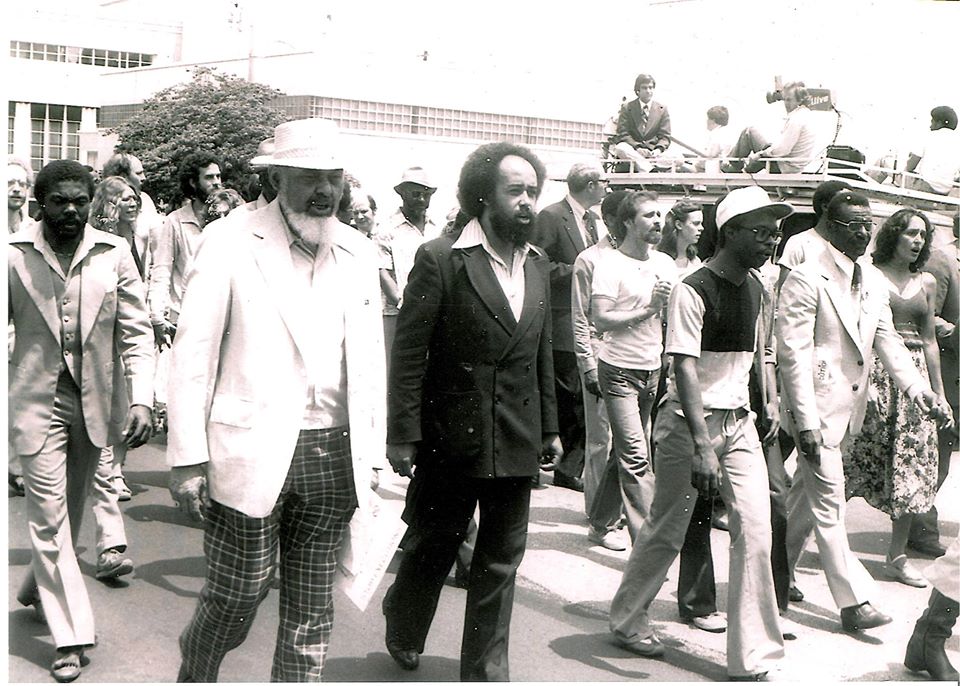

Dr. Charles Lawrence “singing himself away” on the March from Selma to Montgomery, March 25, 1965

A sermon preached for the 4th Sunday of Pentecost

“Whoever welcomes you welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes the one who sent me.” – Matthew 10:40

It was the late 1960’s and it was our anthem. We sang it as we picketed Woolworth’s 5 and Dime in the freezing, wet cold, protesting the Jim Crow laws that kept lunch counters closed to our counterparts six states of Woolworths away. We sang it with our arms folded across our bosoms, holding the hands of one another, rocking on the off beat as we marched in horizontal lines. We sang it while we moved to keep our fears from keeping up with us, to keep the ugliness of our ancestors’ past from determining our children’s future. Siblings sang it in harmony with our parents who were singing it to us as a lullaby, singing to keep our collective courage up, singing it because they knew, as their parents and grandparents knew before them, that living in this imperfect world would require us to know how to disarm our hearts. They were singing it that we might know peacemaking as a way of life and ourselves as children of God. “We shall overcome, we shall overcome, we shall overcome some day. I know that deep in my heart, I do believe, we shall overcome some day.”

In the summer of 1946, our young, handsome parents packed my brother and sister and me into the old Willies for a trip across the rolling hills of Tennessee from Nashville to the Highlander Folk School, 25 or so miles outside of Knoxville in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. Highlander had been founded in the 1930’s as a leadership training institute for those called to the ways of justice-seeking and peacemaking. It was the only place in the South in those years in which, in defiance of Jim Crow laws, blacks and whites regularly met, ate and talked together as equals, and many prominent civil rights leaders, including Ms. Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., attended its workshops on non-violent civil disobedience and anti-segregation tactics and were deeply influenced by them.

To this day, my favorite pictures of our family are those that were taken the summer of 1946 at Highlander Folk School where, at the ages of 3, 2, and not yet one, the seeds of protest and prayer on behalf of justice were planted in our hearts opening us forever to the work that God wants done in the world – the work of arm crossing, off-beat rocking, hand holding, lullaby-singing, sometimes railing against the injustices that separate us from God and one another. The work of disarming our hearts and making peace that all might know themselves as children of God.

There was always a lot of singing at Highlander. “Zilphia Mae Johnson Horton, known as “The Singing Heart of Highlander” had grown up receiving top honors in school in her home town in Arkansas where her father operated a coal mine. Following graduation from college, Zilphia’s interest in the labor movement began to unfold when the Presbyterian minister in town attempted to organize her father’s workers for the Progressive Miner’s Union. After she refused to honor her father’s request to sever her connection with the church’s organizing movement, she was disowned and forced from her home because of what her father called ‘revolutionary Christian attitudes.’”

In 1946, just a few months after our family stayed at Highlander, Zilphia Horton was in Charleston, South Carolina when she heard a song being sung by members of the Food and Tobacco Workers who had walked out on the American Tobacco Company. The predominantly black and female union membership persisted in their strike, picketing for more than five months through the periods of miserably cold and wet weather. To raise drooping spirits, they began to “sing themselves away” with the hymn “I’ll Be All Right Someday,” a song they had learned in their churches. Zilphia Horton carried the song back to the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee to the Highlander Folk School where she taught singer, Guy Carawan[i], who sang it for the first time at a civil rights demonstration in front of a group of protesters in Nashville in late 1959. By then, a second verse had been added as the anthem became the benediction of mass meetings and protests all over the south: “The truth shall make us free”

A third verse, was added one grave night during a sheriff’s raid on Highlander in July 1959. A crowd of mostly black and a few white people filled the hall for Sunday night worship – each person taking a turn preaching, testifying, praying, or raising a song. Toward the end of the meeting, the crowd had joined hands and lifted up “We Shall Overcome.” Just then, a small army of young, white local cops raided the place, brandishing their guns and billy sticks. No respecters of people, they were as they went up in the faces of the worshipers demanding that they stop singing at once. “We are not afraid,” the worshipers sang, spontaneously striking up a new verse, swaying more fervently than ever. The cops tried shouting their orders over the singing, but to no avail. The singing overpowered the intruding authorities. “Well,” said one very green and young policeman to a large black woman with a deep contralto voice. “Well,” he said now drawing himself up to his full height, which was no match for hers. Well, if you have to sing, do you have to sing so loud?!” But the worshipers went on singing themselves into the courage to keep on keeping on. By the early 1960’s, “We Shall Overcome” was being sung all over the South, the country and the world. Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa said, “When we sing ‘We Shall Overcome,’ [what we are protesting is] all that is dehumanizing, what we will overcome is [all that is unjust.]”

“Whoever welcomes you welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes the one who sent me… and whoever gives even a cup of water to one of these little ones – the vulnerable ones who Jesus identifies with – truly I tell you, none of these will lose their reward.” It is Jesus giving a final few words of commissioning to his disciples as he sends them out to proclaim that, at the heart of building God’s Beloved Community is radical, compassionate welcoming of the most vulnerable, the people society has placed on the margins or whose humanity society has denied altogether. His final instructions recall for us the Gospel imperative for social justice, and they point right back to beginning of Jesus’ ministry, to a collection of sayings known as the Beatitudes where Jesus is teaching about the counter-intuitive, countercultural, upside-down nature of the reign of God: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy. Blessed are the peacemakers for they will be called the children of God.”

What “We Shall Overcome” did for the struggle for human rights, the Beatitudes does for our understanding of the nature of the God Movement. “We Shall Overcome,” the anthem of the Civil Rights Movement and the Beatitudes, the anthem of the God Movement, both proclaim that great redeeming reversal in store for all who speak the truth in love on behalf of those who suffer.

Clarence Jordan, founder of Koinonia Farm in Americas Georgia, a pioneering interracial farming community in the heart of the deep south whose witness against racial injustice made it the object of constant hostility, translates the Beatitudes this way: “The spiritually humble are God’s people, for they are citizens of [God’s] new order. They who are deeply concerned are God’s people for they will see their ideas become reality. People of peace and good will are God’s people, for they will be known throughout the land as God’s children. You are all God’s people when others call you names, and harass you and tell all kinds of false tales on you just because you follow me. Be cheerful and good-humored, because your spiritual advantage is great. For that’s the way they treated people of conscience in the past.”[ii]

These uneasy passages are troubling reminders that we live in an unjust world where those who risk their unarmed hearts crying out for justice are often mocked and dismissed as troublemakers. It is tempting to think that “blessed are the peacemakers” means being patient, quietly enduring, suffering souls. But being deeply concerned about God’s people, making peace with our neighbors, hearing others call you names and harass you and tell all kinds of false tales on you just because you follow Jesus is messy business. Following Jesus, it turns out, has the disciples (and has us too) undeniably committed to speaking the truth in love in “protest against all that is unjust about the way things have been, and in protest for”[iii] [the way God intends for them to be.]

When God wants something done about a wrong that needs to be made right, God does not send thunderbolts or wage battles or poll the people, or hold auditions, or, God help us, form commissions and committees. No, when God wants something done, God goes out looking for the most vulnerable places in our lives and in our hearts, the moments and seasons and circumstances that find us despairing, confused, lost, broken, and down on our knees. And there, God troubles the waters. Trouble – that word in scripture that means something is going to get stirred up. Inertia’s day is done. The status quo will be upset. People will be called by God to speak the truth in love, and a movement will begin – a God Movement.

In these last long, weeks and months, the twin forces of the global pandemic and its disproportionate burden on the backs of black and brown and poor communities in our country had already begun to unearth the wounds of systemic racism carved deep in African-American people’s historical memory of our ancestors being stolen from their native land, brought to these shores to be bought and sold as property, and used to build a nation where their descendants would forever struggle to be rightful citizens, but where there was never any intention for us to belong.

Then on May 25th on a street corner in Minneapolis, George Floyd, a gentle giant of a black man – someone’s son, brother, father, grandfather, neighbor, friend, and child of God was murdered. And with the force of more than 400 years of justice denied, a fracture infinitely bigger than the San Andreas fault running deep beneath thick layers of systemic racism erupted in an earthquake of hurt and sorrow. Now black people everywhere are drowning in tsunami-sized waves of exhaustion, the consequence of a life-time of spiritual weight-lifting as each of us lives our own story of being a black person who must spend a lifetime teaching a mostly white world about our experiences of racial injustice. We are down on our collective knees at the wailing wall. We are weary and worn and sad.

Then, first from far away and then moving closer, there is a rumbling and a-shouting and the sound of marching feet. It’s the unmistakable sound of God troubling the waters. People of all ages and races are pouring into the streets of thousands of towns and country-sides all over the country and all over the world, crying out in one voice, “No more!” They are announcing with their signs and their voices and their singing, their courage and their fierce passion that inertia’s day is done. The status quo has forever been turned on its head. People are being called by God to speak the truth in love, and a new God Movement has begun.

Jesus’ call for us to live a life of radical, compassionate welcome is a call for us to protest fiercely against the sin of racism and all that brings death-dealing to the vulnerable children of God. In a recent virtual town meeting with young black activists, President Obama said, “Remember that this country was founded on protest: It is called the American Revolution, and every step of progress in this country, every expansion of freedom of our deepest ideals has been won through efforts that made the status quo uncomfortable.” Our own Episcopal Church was founded in the crucible of protest. Beloved Absalom Jones’ priesthood was formed in the fire of protest. Women’s ordination was birthed in protest. And in the midst of all the troubled waters of these times, the rainbow flag of protest wraps its colorful self around the Supreme Court steps rejoicing in winning long-overdue protections of LGBTQ workers from job discrimination. My grandfather, The Rev. S.A. Morgan, was an Episcopal priest in Vicksburg, Mississippi in the early 1900’s. When my brother and sister and I were growing up, our mother told us stories about how when Grandfather went to call on people in need of healing, he would take her – his young daughter – with him because even though he was a priest of the church, as a black man walking the streets without his little girl beside him, he risked being lynched. Every single day of my priesthood is devoted to protesting the likes of that nightmare because I know that more than a century later, that fear is still black people’s daily reality.

With all that we have been through in these weeks and months, indeed in these centuries, can we sing “We are not afraid today?” Can we sing that even in the face of those who would not necessarily include all of us in their definition of Christian, but might disparagingly call us “revolutionary Christians” as Zilphia Horton’s father called her for her witness to truth and justice? Can we sing in the face of those who would consider our protesting unlovable, unholy, unpatriotic? The Greek translation of “Blessed are the merciful” is “blessed are all those with big, unarmed hearts.” Blessed is the black woman contralto of Highlander, overpowering the intruding authorities as she raises her voice in fearless song. She sings because she knows that, for generations to come, we will still be living in a wounded world where the radical, compassionate, welcoming work that God wants done will require of us courageous, spiritually humble, unarmed hearts.

My Brothers and Sisters, Listen! Do you hear what I hear? It’s the rumble of troubled waters right here, right now. It is the sound of the People of God coming out of the wilderness of systemic racism, wading through the troubled waters of our time. It is the sound of something from the foothills of the Smoky Mountains breathing life into our imagination, then into our hearts, and then into our voices. We hear ourselves humming. Then we hear siblings singing with us. Then parents and grandparents and great grandparents and hundreds of thousands of other saints are singing too: We shall overcome. The truth shall make us free. We are not afraid.

Blessed are those who sing a new song, breathing hope into the hurting hearts of a wounded world. Blessed are we who let God break open our already broken hearts to the arm-crossing, hand-holding, off-beat-rocking, lullaby-singing, sometimes shouting work that God wants done. Blessed are the Peacemakers, for we are the children of God.

Let the People say Amen

[i] Guy and Candie Carawan, “We Shall Overcome, Songs of the Southern Freedom Movement,” 1963 Oak Publications, New York, N.Y. p.11

[ii] Clarence Jordan. The Cotton Patch Version of Matthew and John, A Koinonia Publication, Associated Press, N.Y., 1973

[iii] Presiding Bishop Michael Curry